I’m a Scientist, Not a Project Manager

When working alone, executing an experiment that includes a simple task and a few subjects is so mundane that it seems tedious to care about defining clear goals (“my goal is to publish this”), constraints (“the MR room schedule is fully booked”) and deadlines.

But we don’t work like that anymore. The need for larger datasets and replication across sites is already widely accepted. The need for experiment materials, code, and data to be open to the public is also a consensus. Working in collaboration with others facilitates all that, given that we acknowledge both the benefits and the challenges of working with others - whether it is in a small group, or a large consortium.

In recent years, consciousness science has become more and more collaborative. The need for proponents of different schools of thought to work together has been recently highlighted, demonstrating that working in silos leads to incoherent conclusions and a fragmented field. And indeed, researchers are now teaming up to advance the field of consciousness collaboratively (e.g., this Tempelton World Charity Foundation effort, and another example from Tempelton, and Skuldnet).

Yet, working with others requires us to constantly think of others and communicate our needs, capabilities, goals, and constraints. Working with others (even if you agree on your favorite theory of consciousness) can be stressful, exhausting, or intimidating at times. Project management tools can help researchers to navigate the challenges of collaborative work, while gaining the benefits of working with other talented people towards a shared goal.

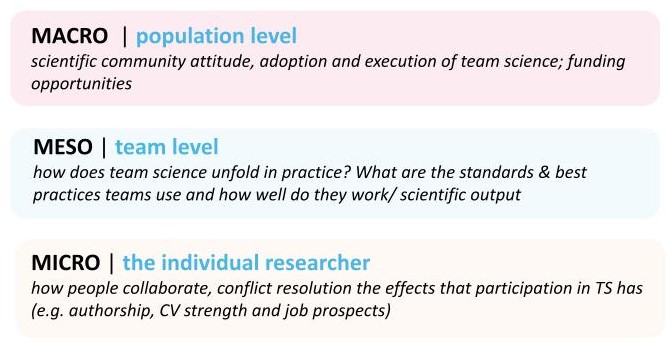

There are several levels of team science, as defined by Börner et al., each providing a different perspective on collaborative project management:

Depending on your role and the size of your collaboration (a project manager in a large consortium, or a researcher in a small collaboration with a couple of peers) you might be interested in different aspects of project management; not everything is relevant to everyone. But how can you tell in advance what is and is not relevant? The answer is that oftentimes, you can’t. This is why in this section, we focus on project management guidelines both at the project level, and at the researcher level.

Project Level

This section focuses on approaches and best practices of assembling and managing an effective team for a collaborative research project.

TL;DR

-

Define the project: Clearly establish the project. What is the end goal of the collaboration? What is the outcome of the scientific endeavour? Most often, these details are outlined in your grant application. Information can be directly extracted from there and put into the Research Management Plan (RMP).

-

Identify project deliverables: This will include high-level deliverables associated with the project. These are the discrete and measurable outputs from your project – again, these are often declared directly in your grant application, and can be used in the Research Management Plan (RMP).

-

Define the work: Once the project is clearly defined, you will need to define the work that is necessary in order to successfully complete the project. This is done by summarizing what work will be done and what work will not be done (a great opportunity to implement convergent/divergent thinking patterns in your team! See Project Management 101). By defining the latter, you create a built-in safeguard against Scope Creep (aka changes, continuous or uncontrolled growth in a project’s scope).

-

Define the Level 1 elements of the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS): level 1 typcially represents the various deliverables of your project. Remember the 100% rule while creating the Level 1 deliverables.

-

Break down each of the Level 1 elements: The process of breaking down Level 1 elements is called decomposition. It consists of breaking down a task into smaller and smaller pieces (tasks > subtasks), applying the 100% rule at each level. At each subsequent level, ask yourself whether further decomposition would improve project management. Continue breaking down the elements until the answer to that question is “no.” When you’ve completed the decomposition process for each element in Level 1, the WBS is complete.

-

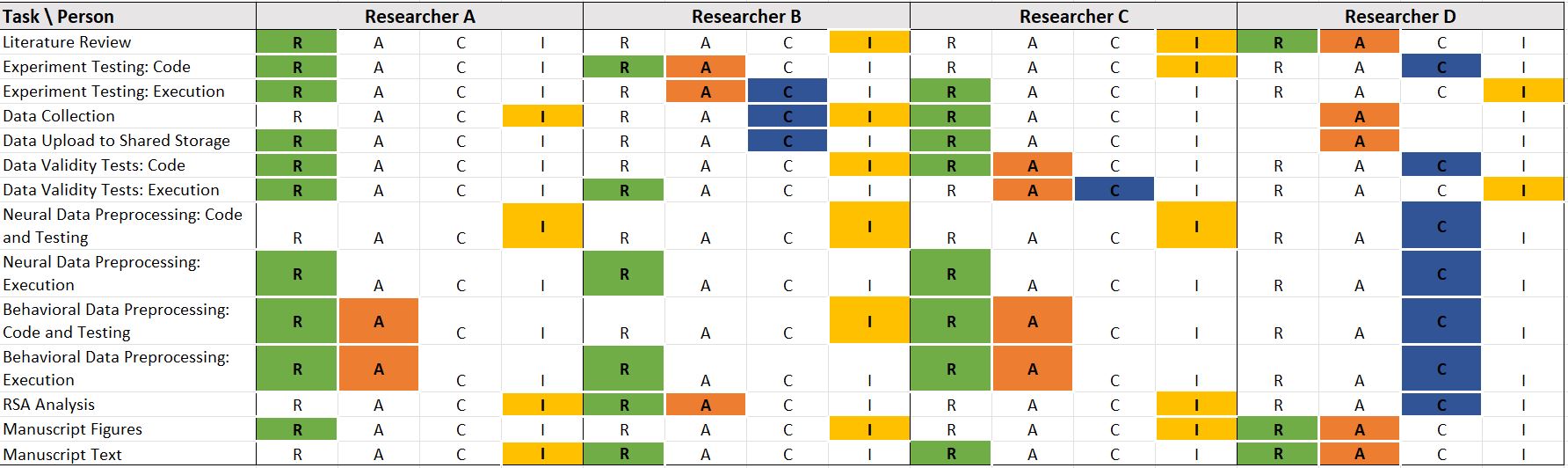

Roles and responsibilities: Identify who is RACI for each work package (see WBS). You will need to determine at which level this is done, depending on project structure (e.g. smaller teams and smaller projects probably only need RACI at level 1, whereas larger more complex projects may have different people working on different parts. Note that you will need to establish clear communication procedures such that collaborators are all on the same page.

-

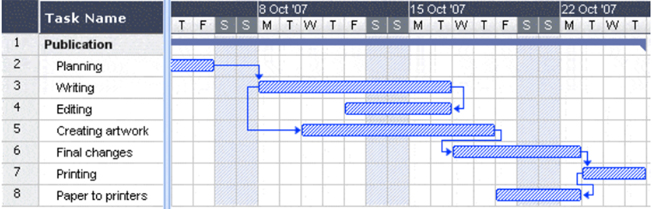

Create a Gantt chart to accompany the WBS. A Gantt chart illustrates work packages over time so that you can visualize information related to the schedule of the project and its various activities. Importantly, it allows to see the interdependencies between tasks (e.g., you can’t publish results until you have analyzed and interpreted your data, and you can’t analyze your data until you’ve collected it, and so on). In other words, a Gantt chart maps the logical steps that need to be followed.

-

Governance: instantiating governing bodies and policies within a team is critical for declaring, monitoring and controlling the ‘rules of the game’. This typically starts with the RMP and is followed up with specific policies for different facets of the team (for example: authorship & contributions, conflict resolution, code of conduct, ethics, diversity & inclusivity, membership policies).

-

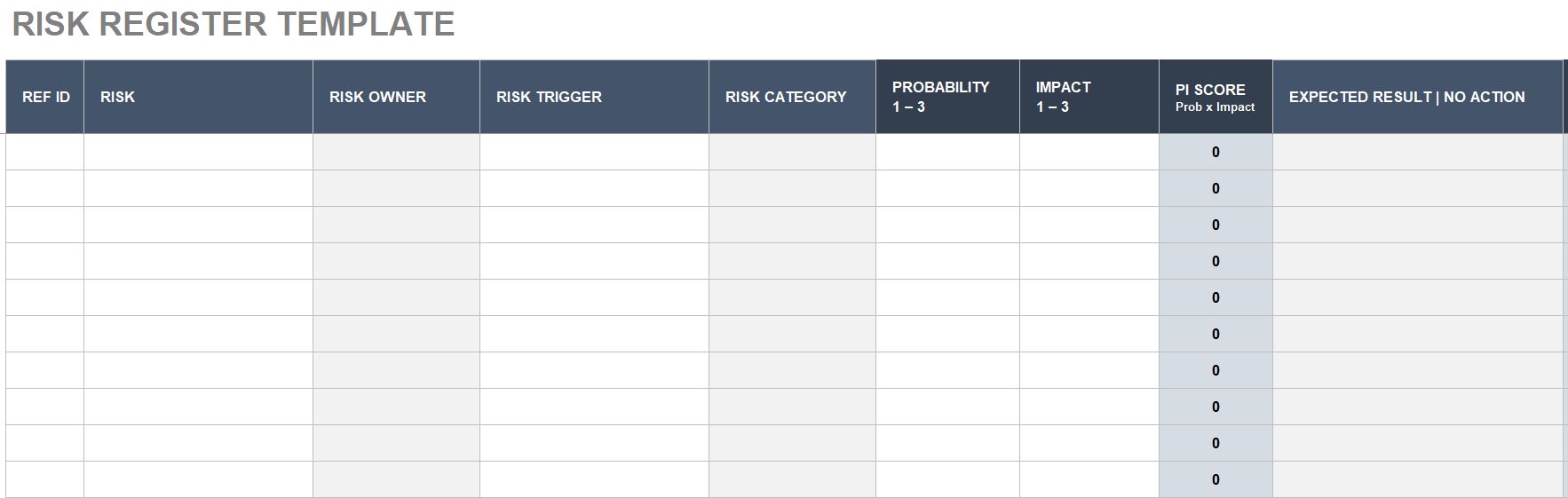

Risk Management: all projects embody risks, at varying levels of impact and probability. Identify the risks, map them in accordance to a Risk Matrix and then devise a plan accordingly. Revisit it often and keep this document updated; Your future self will thank you.

-

Don’t forget about life beyond the project. We all know that research is osmotic and continuous, yet a project is finite. Be sure you have a plan for post-project and have a point of view that includes both what you are working on now and what’s next.

The Science of Team Science

“Team science (TS) is a collaborative effort to address a scientific challenge that leverages the strengths and expertise of professionals trained in different fields” (Börner et al.)

The science of team science (SciTS) is a research discipline focusing on improving team science by developing tools and techniques to recruit, retain and support researchers working in collaboration. Each level of team science (macro, meso, micro) provides different insights about team science. We highly recomment reading the paper and get more information in the INSCiTS website to get familiarized with this domain.

I’m a PI, who has the time?

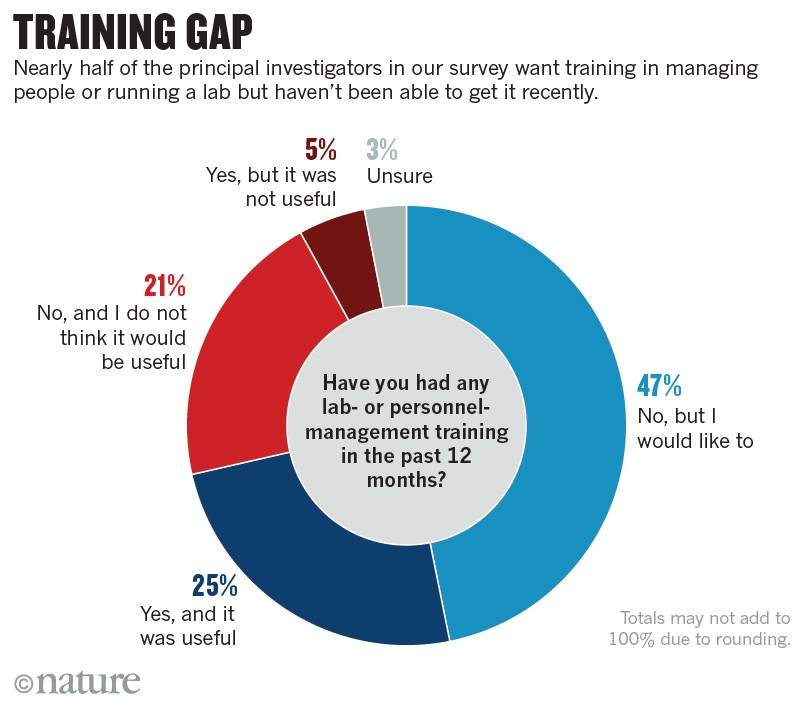

A 2018 Nature survey of 3200 researchers revealed that almost half the PI’s did not have, but would like, formal management training and about a quarter had some training and thought it was useful. However, the remaining portion did not particularly have an interest or shared value for management training.

Science management is critical, and while most researchers do not have the time or that is necessary to obtain formal leadership and management training, it can make or break a collaborative research project. Moreover, it is highly recommended that any large-scale collaborative project reserves a spot on the team for a trained Project Manager (PM). Though, these types of people are rare. Experience has demonstrated that science-centric projects greatly benefit from having a PM that understands the science, as well as imparts the capacity to manage a project.

Here the aim is not to instruct a researcher on yet another “chore” they need to take care of (amidst the long list of already competing priorities e.g., secure funding, manage a lab, publication pressure, open science and FAIRness, teaching duties, conferences). The goal is to provide tools to facilitate collaborative work in a way that will be as painless as possible, as well as concretize the notion that management in science, especially in collaborations, is necessary.

Building a Team

When assembling a team for a collaborative research project, it is important to ensure that collaborators are:

- The same: The sense that the collaborative goal is meaningful, and wanting to take part in working together is key.

- Different: Diversity is important when working in a team. Collaboration between researchers with different expertise harness an immense opportunity not only for efficient work, but also for team members to learn from one another. Researchers who think differently from one another can help improve the research project’s outcome by broading the scope of knowledge and ideas that emerge. Being on a team where everyone agrees all the time should be a warning sign that something is wrong.

Mo’ opinions, mo’ problems

Varying types of thinking within a team can also pose a great social challenge that might result in conflicts or an uncomfortable environment where researchers feel that criticism is not welcome or that their opinions are not heard; or on the other hand, that they are being stimulate creative thought; debates can actually help to identify new opportunities, assess an idea from multiple perspectives, and provide an opportunity to learn from others. Thus, it is important to identify the right times to facilitate discussions that encourage divergent thinking (for example, when thinking about an experiment’s design, when looking for a solution to an issue). Adversarial collaborations, as Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahaneman describes, are a proof of that.

On the other hand, to achieve the research project’s goal efficiently, it is important to balance divergent thinking with convergent thinking; when making plans and setting goals, divergent thinking can leave room for ambiguity about the future steps and tasks that need to be done. Thus, convergent thinking is important to ensure every researcher is clear about the future steps in the collaborative project, and their role in each of these steps.

To demonstrate, here is an example of balancing divergent and convergent thinking styles when selecting the members of the scientific advisory board:

- Discover : have members of the team come together and create a list of all the potential professionals; each person will bring with them their own networks and areas of expertise and enable everyone to put forth their options (Divergent)

- Define: clearly and concisely define the types of role/expertise that the research group requires from those that will fill the seats of the advisory board (Convergent)

- Deduce: outline the skills and benefits each of the individuals bring; you will already begin to see who potentially fits the bill (Divergent)

- Determine: as bringing together steps 2 and 3, you will begin to see most suitable people for the advisory board and objective reasons for why they would be selected (Convergent)

Managing A Collaborative Research Project

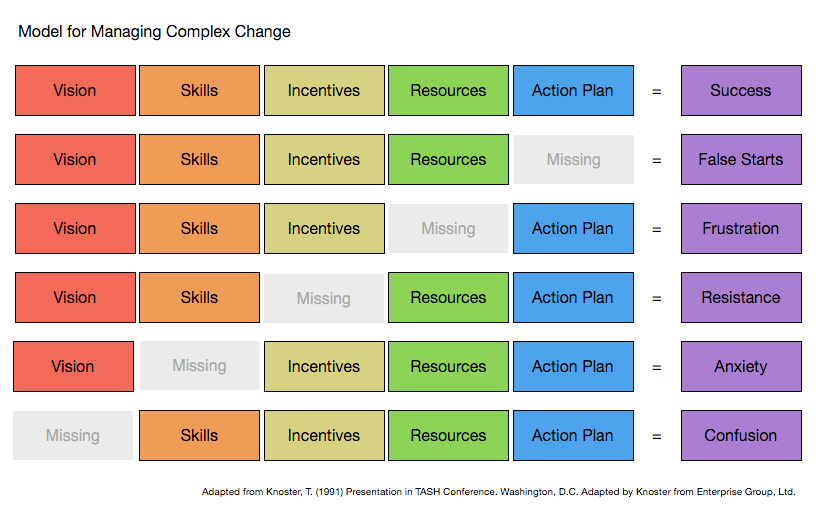

The Knoster Model for Managing Complex Change (Knoster, Villa, and Thousand) describe a framework to bring about and manage complex change.

The same components apply when assembling a team of researchers for a collaborative research project:

The same components apply when assembling a team of researchers for a collaborative research project:

- Lacking vision, a shared goal that guides all researchers towards the desired outcome, generates confusion among collaborators.

- Lacking the skills necessary to realize the shared vision also leads to failure; this is why it is crucial for collaborators to have different areas of expertise that are relevant to the research project.

- Lacking incentives that keep the collaborators motivated to be involved can lead to “gradual change”, or in the research collaboration case, to slower progress instead of efficiency.

- Lacking the resources (time, money, equipment) leads to frustrations, because the collaboration has a goal and a plan to accomplish it, but no resources to get the job done.

- Lacking an action plan, a clear list of steps that can be accomplished one by one, leads to false starts; researchers take off in a certain direction, only to realize that an important step was skipped (forcing them to stop their progress and go back and take care of it), or that there was no point in that direction to begin with. This is why convergent thinking and planning are crucial.

Project Management 101

What is a project?

A project is defined as “a temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique project service or results. Projects are temporary and close down on the completion of the work they were chartered to deliver.” (Project Management Book of Knowledge (PMBOK))

Collaborative research is a type of project; it has a result (a certain hypothesis to be tested, or other initiatives) and it is temporary (as collaborators work together until the goal is reached). Thus, when referring to “projects” below, we refer to a a scientific endavor taken by several researchers.

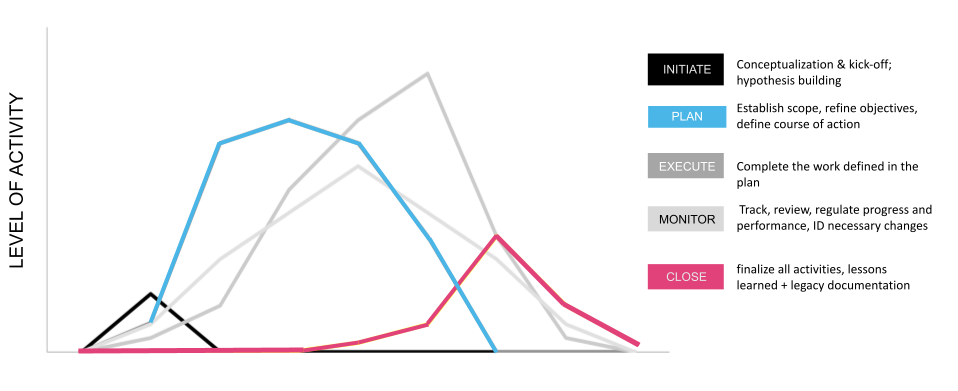

Project Life Cycle

Central to formal project management is the project lifecycle and understanding how to carry out each stage with the greatest amount of efficacy can determine the success of your project.

A project plan (for scientific needs, research management plan, see below) is not typically expected or required of scientific collaborations, especially in smaller scales. However, devising a plan is key to developing an effective research workflow. An important thing to keep in mind is that other than the initiation phase, all other phases (planning, execution, and monitoring) are continuously active throughout the collaborative project; there isn’t a stage when planning is done; there are always activities and steps that require consistent monitoring and updating. As Dwight Eisenhower stated, “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

How do we measure a research project’s success?

The three pillars of measuring the success of the scientific study are:

- Time: the turnaround of the study, in that it’s done in time for it to be relevant, or within a given funding period/per some fixed deadline (e.g. an event)

- Cost: as funding resources have limits

- Scope: whether the project achieved what it set out to do (rather than lost focus somewhere along the way, doing things that were not originally intended)

The project management aspect of a collaborative research project is focused on ensuring these three factors are managed and optimized. The tools and techniques below can help you achieve these goals, even without experience as a project manager. Nevertheless, depending on the size of your collaboration and the resources you have at hand, it might be worthwhile to hire a professional scientific project manager.

Communication

Probably the most important aspect of any collaborative work is communication. And much like the theoretical hypothesis, analysis plans and task timelines, the establishment of communication between collaborators needs to be planned:

- How: what are the communication channels the researchers use? Reminder: when working with teams that cross juristications, there may be communication tool limitations (e.g., some common softwares are not GDPR compliant yielding usability issues in the EU; China imposes restrictions to access to some platforms and changes over time, with new bans imposed at any time).

- When: what is the frequency of collaborators’ meetings? Setting a schedule for meetings (that considers time zone differences when relevant) helps in establishing regular communication among collaborators.

- What: expectations shall be shared about the purpose of each meeting (e.g., some meetings are used for progress updates, others are for project planning). Meeting format should be deliberate and always align with the ‘what’ (e.g. in-person is necessary for some instances, zoom is good for others, sometimes even an ad hoc phone call is enough). Setting an agenda and sharing it ahead of any meeting is good practice; this way, everyone has the opportunity to prepare accordingly.

- Why: maintain transparency about the purpose of any meeting is taking place; also an opportunity to assure everyone’s time is being used effectively; if the reason for holding a meeting doesn’t align with the goals or specific work of the project, then reconsider holding (team members would be happier for a last minute cancellation over meeting for no reason :) ).

- Who: who should attend what meetings; what are the responsibilities across collaborators (set meetings, what is expected to be communicated, etc).

Pro Tip: managing a team across time zones requires a good time zone converter: Time and Date - World Clock Meeting Planner (free), Every Time Zone (basic free version).

An excellent exemplar of a Communication Plan comes from the FAIR Workflows group. It includes a clear communication strategy, approach to establish communication, and metrics to measure the effectiveness of communication in a scientific group.

When working in a collaboration that includes researchers from different countries, it is important to be sensitive to cultural differences leading to differences in the way researchers communicate and express themselves. Richard Lewis’ book (“When Cultures Collide”) provides a perspective on the communication styles of different cultures. It is important to understand and accommodate the different cultures, beliefs, norms and working styles of all collaborators.

Tools & Techniques

Key science management tools to implement:

- A documented outline: Governance and Research Management Plan (RMP)

- Work breakdown structure and project management software

- Time management: Gantt charts

Governance and Research Management

Governance

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

Large or small, scientific collaborations require defining the “rules of the game”. For example, how are credit and authorship assigned? How decisions are made, and who is entitled to make them? What is the collaboration’s code of conduct? How is the experiment data shared and published? These are just a few questions that are answered by establishing governing bodies that oversee those aspects of the research project. Once again, even in collaborations of a smaller scale, defining these aspects in advance can prevent tension and frustrations among collaborators at later stages (e.g., the publication stage).

The planning of such aspects can not be overestimated. Without a clear policy about research codes, programming can easily become an uncoordinated nightmare. Without a clear policy regarding data sharing, a proper data infrastructure cannot be set up. A useful example is the International Brain Lab’s (IBL) formal governance structure. It includes explicit policies regarding decision making, credit assignment and authorship, conflict resolution, membership and affiliation, code reproducibility, ethical conduct and more.

Thus, we highly recommend to be explicit and transparent among all collaborators in form of a collaboration agreement: a legal document that identifies the partners / institutions / legal bodies taking part in the collaboration. It defines the research project goal and deliverables, the duration of the collaboration, the policies for exchange of information and data sharing, the expectations regarding publication, ethic conduct and conflict resolution policies.

- Credit and authorship: a useful tool for tracking credit assignment is the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT), which defines 14 roles that describe specific contribution to the scholarly output.

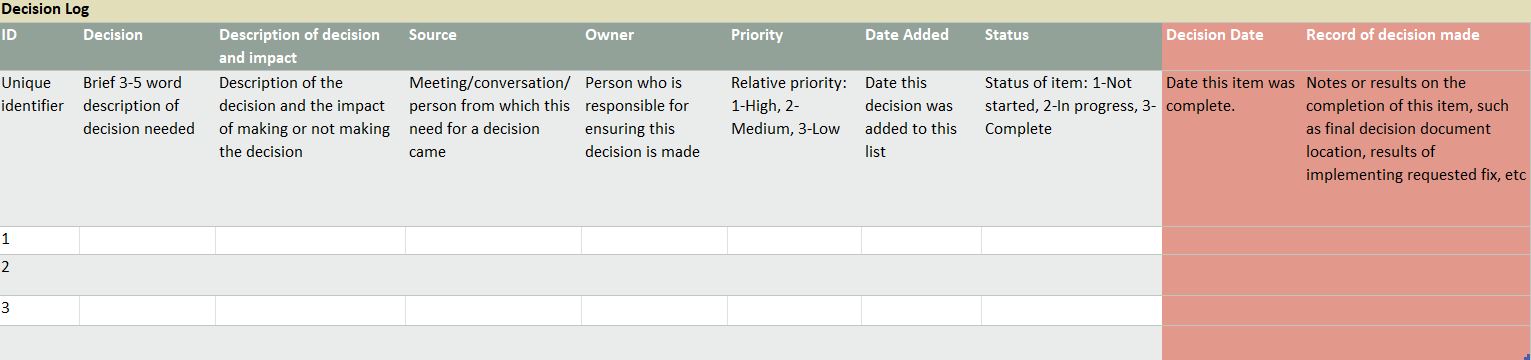

- Decision making: differentiate between scientific, technical and operational decisions, and form a decision making policy for each type (democratic, consensus, hierarchical, etc.). Define who are the decision-makers for each type, as different collaborators have different roles. Also, it is important to establish a timeline for decisions to be made to ensure things don’t drag on. There is often a link between who is ‘Accountable’ (think: RACI) and who makes decisions; that is to say whomever is accountable for a deliverable, is often involved for making final decisions. Be sure to keep a centralized decision log for the collaborators to maintain.

- Membership: Define the types of membership in the research project (collaborators, advisors, support). Take into account the fact the teams are dynamic, and establish mechanisms for collaborators leaving and joining. A good example is IBL’s membership policy.

Research Management Plan

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

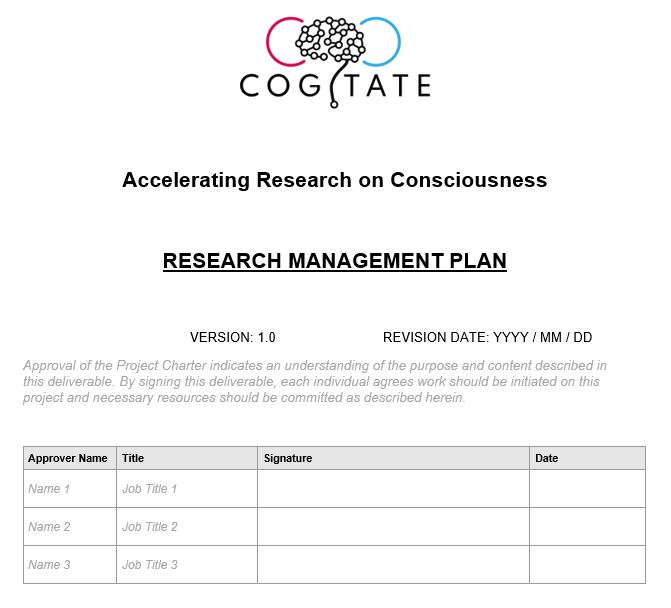

A typical “Project Charter” (a formal document that authorizes the start of a project outside academia) or other commonly used documents (a “Project Management Plan (PMP)”, as per the “Project Management Book of Knowledge (PMBOK)”) are oftentimes not entirely relevant to the way science works. However, that does not mean that a research management plan, outlined ahead of time to guide the collaboration from start to finish, is not a crucial tool. A “Research Management Plan” (RMP) is a robust document that contains all the various pieces of planning and managing that will support a research project. We provide a template below, which of course can be tailored to the needs of a particular project. Note that a project management plan is also good practice even if you work alone; a work breakdown structure, a budget, a schedule and a resource index are always useful. To make it easier to start an RMP, we provide a template that is based on Cogitate’s RMP, that can be customized according to the research collaboration’s specific needs.

Work Breakdown Structure

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

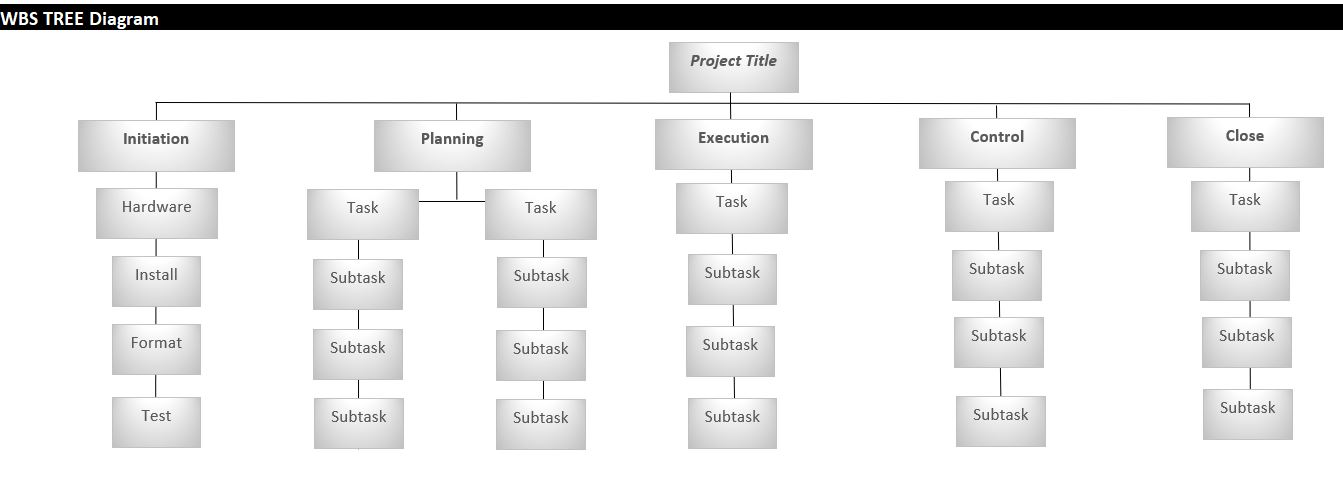

A Research Management Plan gives an overview of the research project. For planning of the various tasks that make up a project, the work that it will take to complete needs to be broken down. That way, researchers can divide and conquer the things that need to be done according to their roles and expertise. For example, the process of piloting and testing an experiment can be broken down into separate tasks (devise a test-plan for the experiment, execute the test plan and report the results, analyze the results and update the experiment accordingly). A Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) is key for defining and tracking those tasks and sub-tasks. A template containing a WBS tree and task list with instructions is provided below.

At the top of the tree (level 1), is the project. Here you provide a statement about what the project aims to deliver, according to SMART goals (see below for more on SMART). Each descending level in the WBS tree represents an increasingly detailed definition of the project work. While the tree provides an overview, the task list helps in specifying the details.

The “100% rule” states that the WBS includes 100% of the work defined by the project scope and captures all deliverables in terms of the work to be completed. The work represented by the activities in each work package must add up to 100% of the work necessary to complete the work package. The sum of the work at the “child” level must equal 100% of the work represented by the “parent” and the WBS should not include any work that falls outside the actual scope of the project, that is, it cannot include more than 100% of the work.

A word on project management software

There is a plethora of project management tools out there; the resources page contains just a few examples. Which one should a researcher use? Currently, there is no “right answer”; no one perfect tool that is tailored to all our needs. Our advice is to pick something that serves the problem you are trying to solve: don’t just choose the hottest tool on the market, as it might not have the functionalities you need. Read about the tool’s capabilities, and decide if it’s right for the needs of the collaborative project. What will the team use it for? (communication? documentation? scheduling?) Choose a platform that:

- You will use

- Your team will use (i.e., it is easy to adopt)

- Serves the appropriate functions you need it to do.

There can (and probably will) be different platform to serve varying needs; as long as everyone are clear about what things should be to tracked and documented in each platform, all is well.

Another word of caution when working in multi-lab collaborations is to consider limitations posed by different countries on certain platforms. Before starting to use a tool, it is important to make sure that all the members of the collaboration can access and operate it. For example: GDPR in the EU, China restrictions that often cannot be overcome by VPN, Personal reasons (e.g. a team member may not be willing to use a particular platform based on values, morals, conflict of interest, etc).

Time management and Gantt charts

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

A Gantt chart is a way of displaying tasks and events over time, to estimate and track the duration they take to be executed.

Not only it helps to visualize different tasks’ durations, Gantt charts are extremely useful in recognizing the dependencies between different work packages; for example, data analysis cannot be programmed without establishing the data infrastructure, as otherwise the inputs and outputs of the analysis are undefined. A simpler dependency is that the analysis cannot be executed until all data has been uploaded to a shared storage.

Thus, in a collaborative project, it is important not only to track individual tasks, but to understand the dependencies across tasks. That way, planning can consider those dependencies to work efficiently and avoid frustrations.

Risk Management

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

All projects impart risks. Most often when we think of risks, we resolve to “what are the bad things that can happen”. But there is also another type of risk – missed opportunities. It is guaranteed that challenges and obstacles will arise that threaten the success of your work and potentially the project at large. Having a well-devised plan for how you will prepare for and respond to these inescapabilities, the more likely your team is to succeed in the end. This is a key coordination tool so team members know, that if X happens, I need to do Y. A risk management plan is essentially a series of glorified if/then statements. And so, it is critical that all projects develop a risk management plan.

The first step of creating a risk registry is identify. Here, you want to list the four different types of risks:

- Known knowns: Things you’re aware of and understand (e.g., repeating the same tasks over-and-over)

- Known unknowns: Things you’re aware of but don’t understand (e.g., I know that patient data collection is unpredictable and so I know I don’t know how long it will take to finish collecting data)

- Unknown knowns: Things you’re not aware of but understand (e.g., biases, surprises)

- Unknown unknowns: Things you’re neither aware of nor understand (e.g., COVID-19)

Once you have a solid list entered into your risk registry, then you will assess each based on the following metrics:

- Probability of (not) happening (P): 5 levels – very unlikely (10%) / unlikely (30%) / possible (50%) / Liekly (70%) / Very likely (90%)

- Quantification of the impact (I): how negative/positive the risk would be if it happened. 5 levels – very low (0.05) / low (0.1) / med (0.2) / high (0.4) / very high (0.8)

- Risk Score = P x I. Then, you can plot the socre on the Risk Matrix (darker = be most prepared and monitor closely // lighter = lower priority

Risk Registry is a living document – add and edit as needed; whatever you do , don’t create it during the planning phase and leave it – this needs to be monitored and controlled throughout the project lifecycle.

Researcher Level

This section focuses on approaches and best practices of being part of a team in a collaborative research project.

TL;DR

-

Know what you are getting into: have a clear plan for your collaboration, even if it’s small and you think you might not need to explicitly outline everything. This saves a lot of uncertainty, tension and confusion. When taking part in a larger effort, be sure to know the collaboration’s plan.

-

Know your role: know exactly what are your tasks, and who is in charge of aspects your work might depend on. Make sure to update the registry if you take on or give up tasks. Baesed on your roles, it is good practice to list to yourself all your goals, so you will be clear on where you’re heading and when you are done with a certain task.

-

Keep track of tasks and decisions: the task might changed based on decisions that were discussed. You might have an answer to a question relevant to one of the things you are responsible for. Keeping track of all the decisions, questions and answers that arise while collaboratively working on your project saves a lot of time and effort.

-

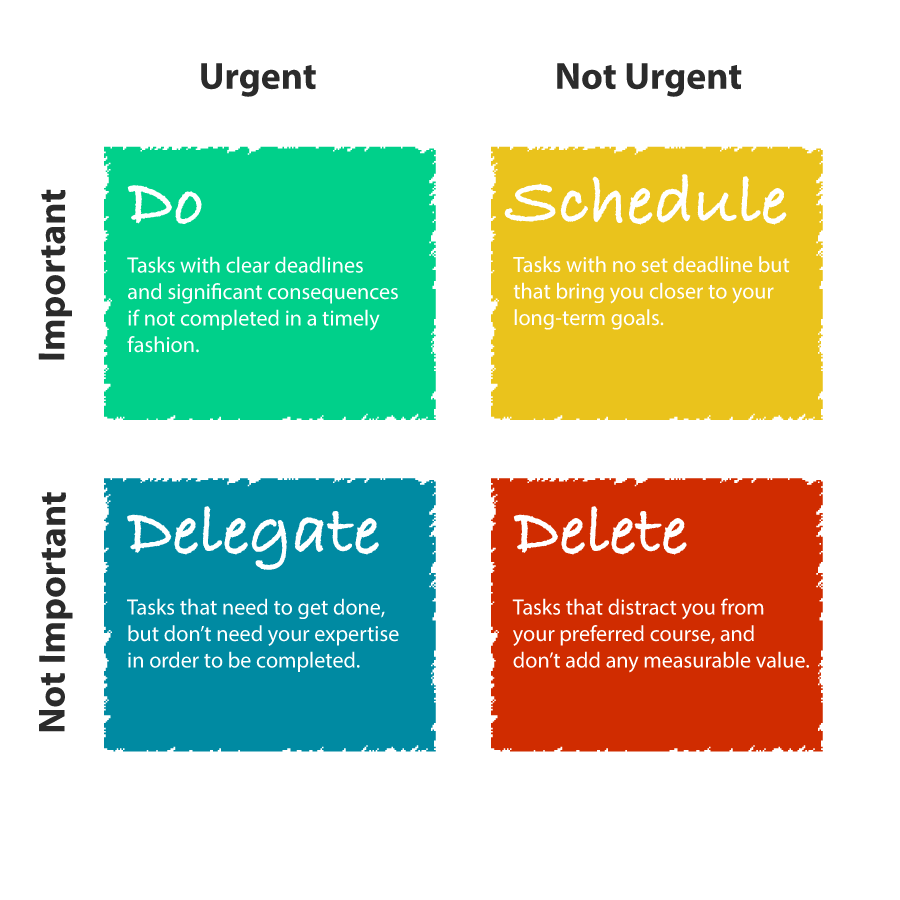

Prioritize: prioritize your tasks based on your roles in them, their urgency and importance. Make sure to update those priorities to avoid known cognitive biases and work effieicntly. This also helps you to understand what’s causing your workload, and what you can do about it.

-

Avoid reinventing the wheel: it’s best to look for existing tools for time and priority management than inventing new systems. Keep that principle in mind when working on your tasks, for example when analyzing the collected data.

-

Don’t forget about the big picture: what you are working towards, really?

-

Don’t forget about life beyond the project. We all know that research is osmotic and continuous, yet a project is finite. Be sure you have a plan for post-project and have a point of view that includes both what you are working on now and what’s next.

Getting started

As researchers in a collaborative project, the managerial part of tracking decisions, dividing up tasks, and planning ahead can seem daunting, or out of the scope of the researcher’s role. Yet, as collaboration entails working with others, it requires us to think of other people in every step we make; from data collection to data analysis, our work, goals and tasks will depend on others. Without planning and management this can be a hurdle; yet, with correct mapping, documentation, and prioritization, all collaborators can gain immensely from working together.

From large to small collaborations, the common starting point is devising a clear, explicit, and as detailed as possible plan. When working on a collaborative study, disagreements and arguments will be inevitable. Unexpected hurdles will rise at the most inconvenient times. However, setting some things from the get-go can alleviate a large portion of frustrations. In addition, to keep the collaboration in track, it is important to create shared habits that facilitate progress. The crucial guiding principles of the collaboration are: be specific, confront uncomfortable topics before they arise, and don’t forget the overarching goal of the project. This is what the Research Management Plan (RMP) is for.

When in a small collaboration, you might be the one devising this plan. Whan joining a large group collaobration, this might be someone else’s role. Yet, there should be such a plan, in some format, where all collaborators can find:

- The collaboration’s goal, start, and finish: having a clear framework agreed upon in advance is the basic step in a collaboration. This also helps to get everyone on the same page. The goals of the collaborative research project should be well defined, and we recommend defining them according to the SMART method.

- The theoretical decisions deriving from the project’s goal: the research hypothesis and the planned way of testing it should be clearly defined. We might not have all the fine details from the get-go, but much like preregistration, there are basic aspects we need to commit to. When working alone these commitments help us improve our research methods; when working in a collaboration, these help to establish clarity and a shared understanding of the project.

- The organizational structure: get to know your collaborators and their areas of expertise and decide who’s in charge of what. A collaboration is a shared journey, but dividing the work is essential. Things that don’t have a clearly defined point-person are danger zones of miscommunication, missed deadlines, and confusion. Knowing who to adhere to in certain topics, while in others you are the decision-maker, promotes efficiency and a sense of individual ownership within the collaboration. We all have our own professional strengths and weaknesses. Acknowledging them early on can help plan how work will be divided, and whether there is a lack of required expertise in one or more aspects of the project. Transparency across collaborators about their expertise and weaknesses facilitates a fair, efficient hierarchy and helps to define who’s in charge of what (see below).

- The sharing policy: as mentioned in the data infrastructure chapter, data sharing, even among collaborators, is a legal ordeal that needs to be taken care of and planned ahead of time. Whenever more than one institution is involved, the specifics of what can and cannot be shared, and in what form, set limitations on all future decisions about data collection and analysis.

- Standardization: as different researchers have varying sets of working habits, a collaborative effort must establish a shared set of tools and practices for standardizing materials across sites. These include things like the format of the data infrastructure and the programming language used for data processing and analyses. From our experience, though seem technical, these decisions need to be made at some point, and it is very hard to switch over to the agreed-upon standard once work has already been done. To save time and effort, these aspects need to be spelled out in advance, based on the knowledge and capabilities of the collaborators.

SMART Goals

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

When defining goals for the collaborative research project, it’s good practice to go by the SMART method.

- Specific: Objectives should provide the “who” and “what” of your study.

- Measurable: How would the goals be measured? How do you know that a step (data collection, analysis) is done? Unless they can be measured, it is very hard to define when goals are met. As the aims were specifically defined, there is also a need to be explicit on what are the collaborators working towards.

- Attainable: The goals that are defined should be achievable within a given time frame and with available resources. Both the time frame and the resources are also things that are crucial to lay out in advance, even when the collaboration is small (where usually researchers are not required for these ahead of time).

- Relevant: The collaboration goals are useful when they accurately address the scope of the collaboration and steps that can be taken within the given time frame. Goals that are directly related to the study goal will not help achieve it.

- Time Based: Goals should provide a time frame indicating when will the goal be measured, or a time by which the objective will be met. This can (and redommended to) be further specified by a Gantt chart. Including a time frame in the objectives helps in planning and evaluating study progress.

How do I start?

- Identify the issue you are trying to solve. It can be the overarching goal of your collaboration, or your own personal goal as a researcher taking part in one.

- Rephrase your problem into a question you can answer.; this helps to define what you want to measure and what results or outcomes will tell you you’ve been successful.

- Determine the relevance of the issue to the collaboration you are taking part in; this will also help to prioritize this goal later on.

- Estimate the time it will take you to reach the goal, finish the task, and attain the measurable success.

SMART goals are an efficient way to create yourself a “guiding light” in a collaboration.

- If you are collaborating with another researcher, this can help make sure you are on the same page.

- If you are in a project management role in a collaborative effort, SMART goals are the first step in devising a Work Breakdown Structure based on a strong Research Management Plan.

- If you are a reseacher taking part in a large collaboration, defining your personal SMART goals based on your role in the project can help you work efficiently and make sure you don’t deviate from what you are trying to accomplish. This is also strongly related to the division of responsibility and accountability of different people in a research project, which is the next part.

Know Who’s in Charge: RACI

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

A responsibility management matrix (or RACI; Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, or Informed) is a simple visualization helping to summarize the collaborator’s roles with respect to different aspects of the collaboration.

- Responsible: for doing the work to complete the task. Usually, there is more than one “R” per aspect, as the study is collaborative. In a large collaboration, this can be a whole team.

- Accountable: Delegates the work and reviews the task to approve it is indeed complete.

- Consulted: Provides input, and can help make progress based on their expertise.

- Informed: Needs to be kept in the loop with respect to progress.

Again, there are many formats, and RACI is far from the only one. This is used as a demonstration for implementing project management tools for collaborative research. Using a technique you are comfortable with, it is important to establish each researcher’s involvement, responsibility and accountability regarding different aspects of the study.

Credit, authorship, and helping others

Based on the assigned roles and responsibilities (with the use of RACI) you understand and solidify what you are accounted for as well as what you need to get credit for. Sometimes, as the collaborative work progresses, there can be situations during which there is a feeling of “all hands on deck” despite well-defined roles and accountabilities. This approach can lead to frustrations, as working on something you are not responsible or accountable for can:

- Create tension with whoever is responsible or accountable for the job.

- Hold you back on the things you are responsible or accountable for.

- Create expectation for you to be involved in future work on this job, without a clear definition of your part in it, with the respective acknowledgement of your contribution.

Helping your peers is important. Collaborators are all in this together, and of course when someone is stuck or needs your expertise you should lend a hand. But know the limit between helping and taking over a task that is not yours to do (even if you can do it). The main take-home message of the responsibility assignment in a collaborative project is that it is not only to define what the researcher should do; it also defines what the researcher is not supposed to be doing. Any change in your contributions to a collaborative project needs to be followed with an update on:

- Your RACI roles: collaborators’ expectations from you, and assessement of your performance, rely on the job they know you need to do. If you are actually doing more than people know about, it might seem like you are behind on the known tasks, when actually you have a lot on your plate. Make sure your roles are up to date with what you actually are working on.

- The timelines of your responsibilities: as you have your own responsibilities and need to prioritize your own tasks. As happens in life - things don’t always go as planned. One day you might think you can spare some time taking over a task you were not assigned with, and the next day something happens, and you find yourself in over your head. When ageering to take on new tasks, make sure to consider your timelines and priorities.

- The acknowledgement of your contribution: When there are disparities between who was supposed to do the work and who ended up doing it, acknowledgement for your work might be ignored or create frustrations among you and your peers. Make sure that the your contribution is known before it is time for actual credit assignment.

Know where to draw the line between anecdotal pitching in and taking over a task you were not assigned to just because you are capable of executing it. Sometimes, to make progress, it needs to be clear what is taken care of and what keeps missing the target. This also helps in making decisions and plans that rely on all the people involved.

Keep Track of Tasks and Decisions

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

We tend to write things down either at the beginning of new endavours, or when putting everything up for a manuscript. Not only it is a bad habit, when working with others it is impossible to work this way. Failing to put decisions and progress down in writing (“I remember what I did”, “I’ll do it later”) leads to redundant discussions, repetitive work, and frustrations. Communication and meetings among collaborators are important, but documentation is different and does not include just the things you communicate to others. When decisions are made, when progress is made, when questions are pending and we need to remember to get an answer for them - there is a need for a centralized document that concetrates important information, insights and decisions reached during the collaboration. This saves a lot of redundant communication (e.g., getting lost in messages trying to find what was decided, trying to remember the final decision reached in a meeting), time and future frustration.

We summarize key things that from our experience need to be documented (as sadly, we know what it’s like when some of them are not). This might not be exhaustive, but we don’t mean it to be - our goal is to establish what we believe is the bare minimum required for scientists to work together efficiently and happily.

First and foremost, you need to decide on a single platform to keep track of your tasks, and one to keep track of decisions (can be the same one, can be different). There are plenty of tools that provide help with that, but all of them are worthless unless the collaborators use them wisely.

- Choose as few tools as possible, and stick to them: documentation and task-tracking tools tend to proliferate as projects last longer and have more collaborators. Naturally, each researcher has their favorite way of working, but at the end of the day if multiple tools will be used, no one will benefit from them. The goal of documentation is to centralize knowledge, to simplify tasks and avoid endless discussions.

- Read what you document: this may sound trivial, but the important thing about tracking past decisions is to prevent re-iterating questions and decisions repeatedly. When writing, be as explicit as possible, and try to convince your future self that the decision was justified. But, more importantly, make sure your future self is reminded of that decision, and knows where to find it.

- Know when something’s working, and when it’s not: if the methods you chose for documentation work for you and your peers (you write down decisions, you consult those docs when you meet and discuss, navigating and updating them is not a pain, all the collaborators use it), then stick with it. None of the existing tools is perfect, and we can always find the flaws (“oh, I wish they had that feature!”). There’s no need to fix what isn’t broken. But if the method you chose does not work - not all collaborators use it, it does not serve you in discussions and decision-making processes - then know when to switch. The emphasis here is switch - as adding more and more tools (instead of migrating from one solution to another) will do more harm than good.

Remember: documenting is always a drag. These extra couple of minutes at most times seem redundant. Yet, this small investment is worth the hours and days you and your collaborators will have to spend months later, going back to old topics and wasting your time figuring things out all over again.

Visit the resources page for examples for task tracking tools. Also, below is a simple template for keeping a decision log, which requires no fancy tools:

Prioritize

(Back to project level TL;DR) (Back to researcher level TL;DR)

Once documenting decisions and keeping track with tasks, the abundance of tasks can seem intimidating. When working collaboratively, tasks have different priorities depending on the researchers accountable, responsible, consulted and informed. All collaborators have the same overarching goal (the aim of the collaboration, the final product), but the load and scope of work varies depending on the researcher’s role. Thus, as a collaborator, you have your own deadlines, time lines and tasks - and balancing among them is key. This is important as research showed that cognitive biases hinder our time management skills:

- Optimism bias: we overestimate our likelihood of experiencing positive events and underestimate our likelihood of experiencing negative events. While this approach makes sense, it leads us to believe we are going to be more efficient than we are, so we might take on a task that is too big for us to handle alone. (Sharot, 2011)

- Projection bias: when we take on a task, our current emotional state is optimistic. We mistakenly assume that we will continue to feel well-rested and motivated as we continue to work on the task, and will continue to work at the same level. This leads to a tendency to take on big tasks, inaccurately projecting that we will continue to feel optimistic in the future. (Kaufmann, 2021)

- Bikeshedding (Parkinson’s law of triviality): describes our tendency to spend too much time on menial/trivial tasks because it is easier to have an opinion on simpler matters than to try and tackle the complex/immportant ones. (Farnam Street, 2020)

- Restraint bias: we overestimate the level of control we have over our impulse behaviors and underestimate how distracted we might get while trying to complete our to-do list. (Nordgren et al., 2009)

With all these biases (and all the tasks we need to complete), it difficult to know what to prioritize. Once again, there are many ways and methods to try and prioritize our workload. A popular one is called the Eisenhower Matrix, and it is based on balancing urgent and important tasks.

The columns are labelled ‘urgent’ and ‘not urgent’, and the rows are labelled ‘important’ and ‘not important’. Depending on the category a task falls into, there are strategies for how best to deal it. Tasks that are both urgent and important should be done immediately. Tasks that are important, but not urgent, should be explicitly scheduled such that progress in them will not be neglected (as they will move to “urgent” if we forget about them for too long). Tasks that are urgent but not important should be delegated to someone else, if possible. Tasks that are neither urgent nor important should be deleted altogether.

The decisions you should reconsider when impractical

We make plans, and we document them, and we prioritize them. Then, reality hits: even with the most careful planning and the best of intentions, things don’t go as planned. This doesn’t mean the hard work we have to put in organizing, documenting and prioritizing is a waste of time; without it, it will be very hard to move forward collaboratively. But once things don’t go as planned (and at some point, they won’t), it’s important to remain agile.

As collaborations don’t depend on a single collaborator and don’t always go your way, it can be helpful to actually plan for things not to go as planned. When setting up deadlines or the time it will take to complete a task, consider the other collaborators on whom the task depends on; think about possible hurdles you might face, and take into account that there will be some factors unknown to you at the moment that can create hardships. Then, your estimation for how long a task will take to complete will be realistic (instead of ideal and unattainable). This will both prevent frustrations (always feeling behind the deadlines) and will allow collaborators to plan ahead.

And when the time comes, and plans go sideways, it’s important to know what needs to be let go of. Separate the “nice to have”, impractical goals from the ones that actually push you towards your goal; edit your Eisenhower Matrix (or other priority list).

A note about tasks and planning: It’s important to set big goals’ deadlines and plan your time accordingly. But sometimes, deadline can hinder progress rather than facilitating it. Setting too many deadlines can create unrealistic expectations that are hard to keep, leading to deadlines being arbitrarily set and routinely missed. Then, when a real deadline comes (the end of the project being kind of an important one), you might find yourselves behind on many fronts at once. Thus, keep track of the timelines of your goals, and the time it takes you and your peers to complete tasks. Make sure to document progress. But - try to avoid setting too many intermediate goals; ones that are meant just to “show something” to those who should be informed. Instead, share things once they are finalized and truely ready to be assessed (or, require deliberation and decision making in a group forum).

The decisions you have to stick to - no matter what

Knowing the collaboration’s priorities and main goal, you should be able to separate the relevant goals and tasks from the irrelevant ones. It’s important to stick to the ones that are absolutely crucial for the project to succeed - again, with success being pre-defined and explicit.

Differentiate personal from project goals

It’s important to balance between shared goals and personal goals. There are many benefits one can gain from working collaboratively with others, and indeed you should be able to grow personally as a researcher from working in a shared project. Navigate the project in a way that advances you towards your personal goals, but keep in mind that if the collaboration is stuck - you (and others) are stuck as well. There is no one method that fits all, but when prioritizing, however you do it, it’s important to think about this balance.

Avoid Reinventing the Wheel

On every step of a collaborative process, this advice is true, relevant and important. From documenting, to planning, to processing and analyzing data - it is highly likely that the majority of the things you need have already been created. You might have to mix & match some tools and methods together to customize things for your project, but start by looking for existing solutions before trying to create one yourself.

Don’t Forget About the Big Picture

When swamped with work, tasks, deadlines and meetings, it is sometimes hard to see things in perspective and think about our endgoal. From time to time, it is important for collaborators in the project to think about the future (e.g., the end of the project), and update the plans, workflows, or communication as you go to proceed towards the goal.